Max Kossek and Ian Stewart

Lagging domestic microelectronics production has forced Russia to continue to rely on foreign-sourced electronics for its weapon systems. This article examines where Russia imports these electronics from and how this has shifted since the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Hong Kong and China have become the main suppliers post-invasion, though the electronics are still predominantly Western-branded electronics. Sources differ over the scale of Russian imports. Several indicators point to the increasing cost and complexity of Russian procurement, demonstrating the effectiveness of sanctions and export controls.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the U.S. and its allies have imposed strict export controls, and a series of sanctions targeting sectors and entities involved in furthering Russia’s military aims. The U.S., European Union, Japan, and United Kingdom have also jointly developed a Common High Priority List (CHPL) of Harmonized Digit (HS)—a classification system of descriptors used to signify different sorts of goods for customs purposes —codes that include items at a high risk of illegal diversion by Russia. This high-priority items list includes various classifications of integrated circuits, microelectronics, and machine tools that Russia struggles to produce itself or views as valuable for its war aims.

Tier 1 items are of the highest priority “due to their critical role in the production of advanced Russian precision-guided weapons systems, Russia’s lack of domestic production, and limited global manufacturers”. Four HS codes are included in Tier 1:

-

Electronic integrated circuits as processors and controllers (HS 8542.31);

-

Electronic integrated circuits as memories (HS 8542.32);

-

Electronic integrated circuits as amplifiers (HS 8542.33); and

-

Other types of electronic integrated circuits (HS 8542.39).

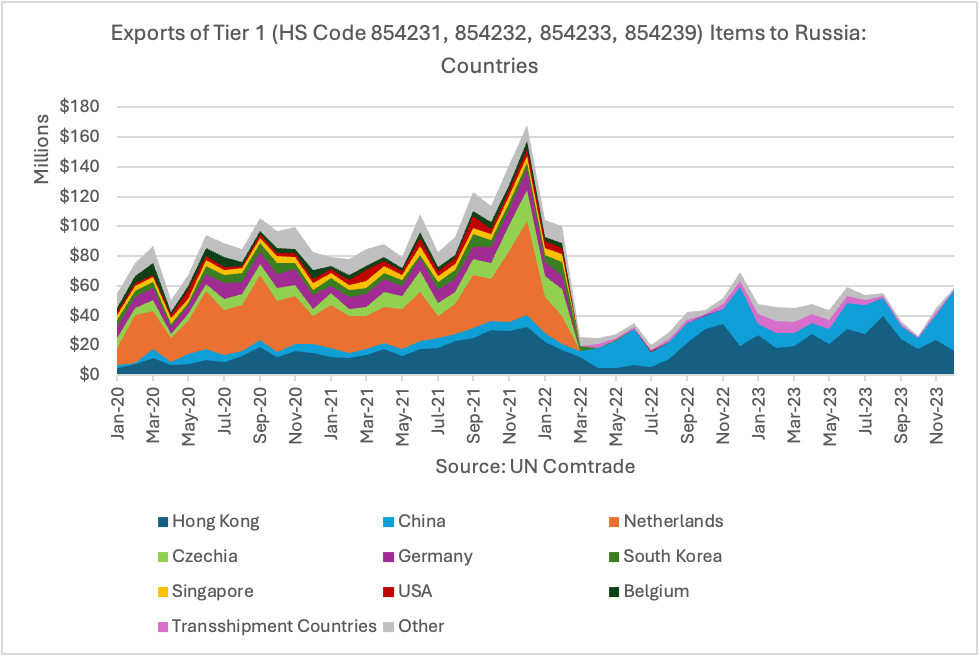

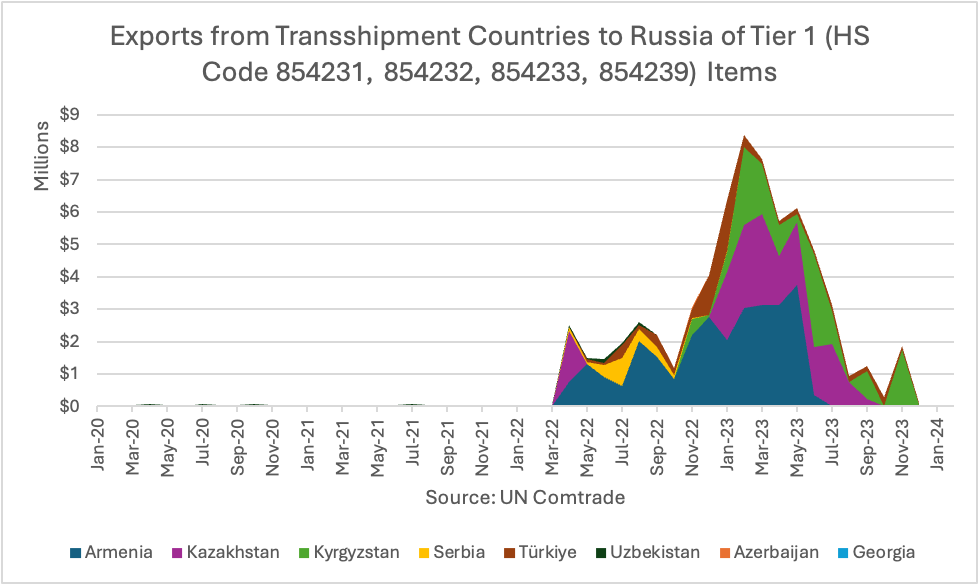

Before 2022, Russia had a diverse set of countries supplying CHPL Tier 1 chips, with monthly imports (based on UN partner country export data) roughly between $80- to $100 million. Figure 1 shows that imports peaked shortly before Russia’s invasion in December 2021 at over $160 million, a possible indication of stockpiling. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there was a sharp drop in imports of Tier 1 items for all countries except for China. After a short adjustment period, Hong Kong, China, and transshipment countries became the main exporters of these items. Transshipment countries, who before the invasion exported virtually no chips to Russia, started reporting exports peaking at almost $10 million per month in February 2023 (see Figure 2).

Figure 1

Figure 2

According to the UN Comtrade data, the increase from Hong Kong and China did not compensate for the decline in overall exports. Exports to Russia of Tier 1 export-controlled items in 2022 and 2023 remained at levels two to three times lower than pre-invasion levels.

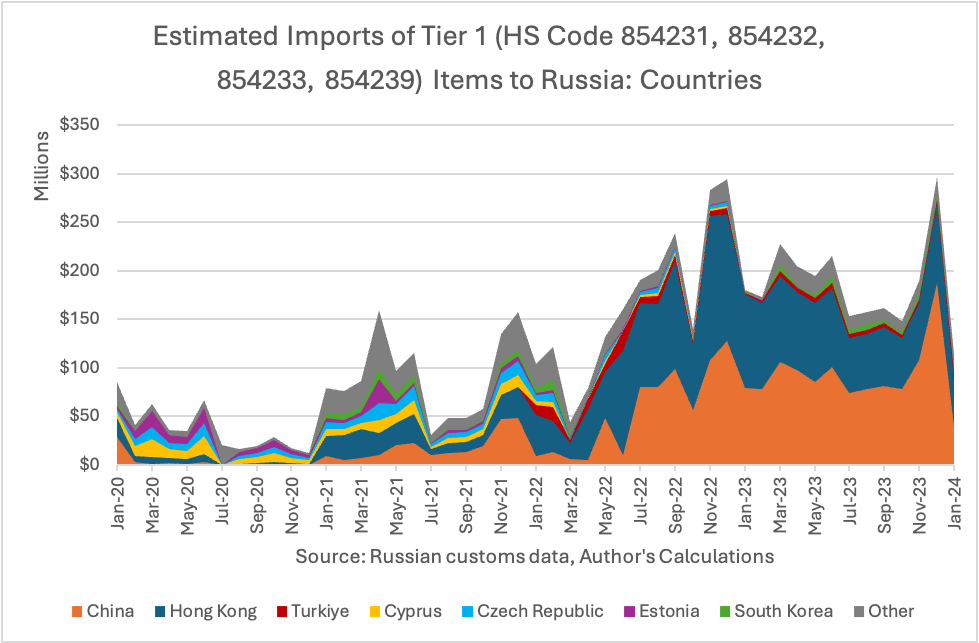

However, this sharp drop in exports in the UN Comtrade data contrasts with Russian imports customs data. Figure 3 shows a clear rise in imports of Tier 1 items after March 2022, most of which came from Hong Kong and China.* Reported imports of Tier 1 items peaked at almost $300 million in the December 2022. In early to mid-2023, imports levelled off to about $200 million per month, which is still significantly higher than the usual levels of $50 to $150 million per month seen in early 2020 and 2021. Imports then rose again towards the end of 2023, close to a peak of $300 million in December 2023.

Figure 3

It appears that most countries have decided to stop exporting these high-priority items to Russia. So, who still reports exports of these items, given the high risk of sanctions? The answer is an ever-evolving cast of ephemeral trading companies, primarily located in Hong Kong and China. The U.S. Treasury Department has already sanctioned most of the biggest suppliers, such as Win Key Limited, Pixel Devices Limited, Tordan Industry Limited, and IMAXChip (all Hong Kong-based).

The same pattern of obfuscation occurs on the Russian side, with companies setting up similar ephemeral front companies whose sole focus is to procure these high-priority microelectronics. New entities appear soon after previous entities are sanctioned, and the cycle repeats.

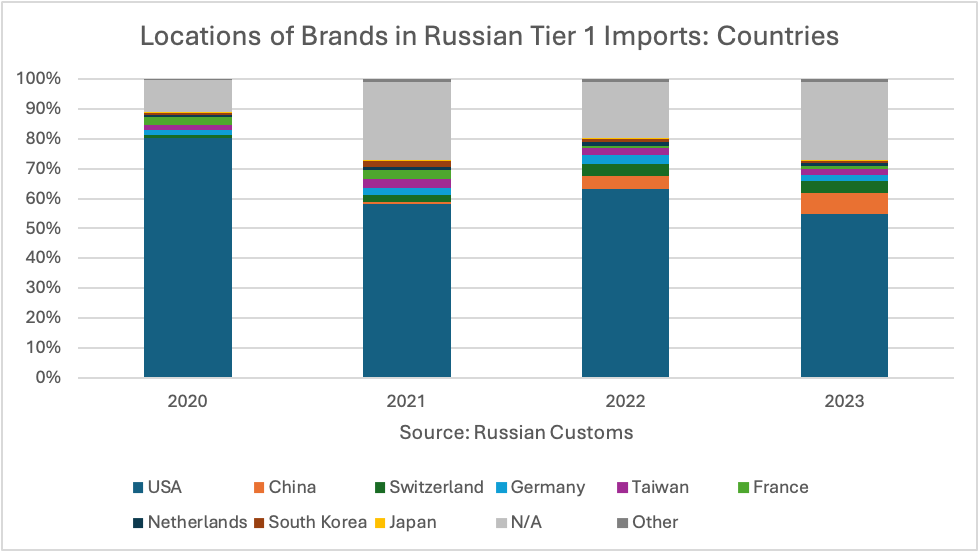

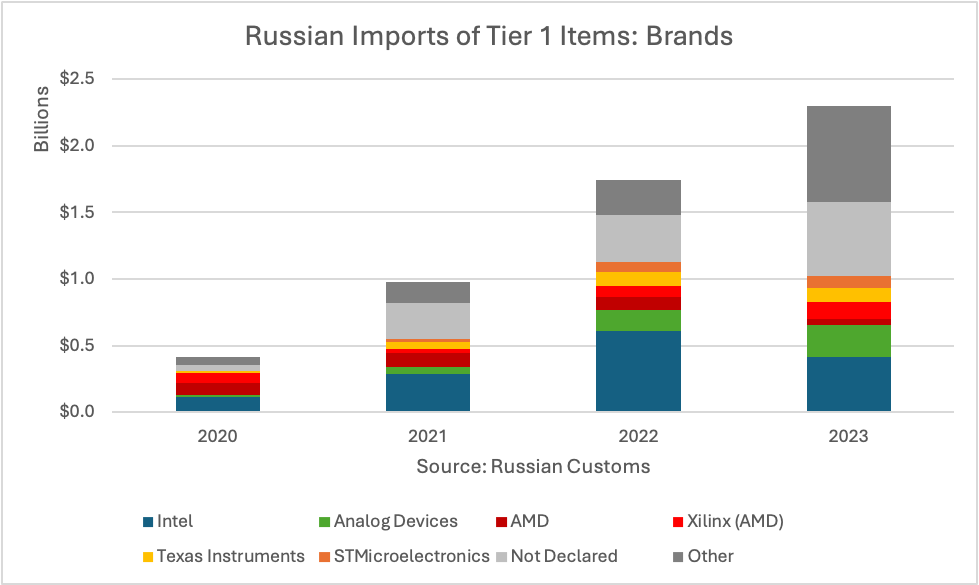

Coinciding with an increase in imports from China, Russia has also imported more chips made by Chinese companies after 2022. But Chinese chips still account for less than 10% of total Tier 1 item imports. Products from U.S. and U.S.-aligned companies continue to make up most of Russia’s imports of integrated circuits (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Chips branded by American companies Intel, Analog Devices, AMD, and Texas Instruments played the largest role. Figure 5 shows that these four companies accounted for about 73.5% in 2020, 53.6% in 2021, and 60.6% in 2022 of Russian Tier 1 imports. In 2023, this share decreased to 40.5%, although there has also been an increase in customs records not declaring the brands of the imported items.

Figure 5

Most U.S. manufacturers have stated that they comply with applicable export controls, halted sales to Russia, and have tried to improve their due diligence processes. Nevertheless, many of these components continue to reach Russia. Most microchips are not export-controlled except for a small subset of countries, such as Russia, North Korea, China, and Iran. The small size of microchips also makes them easier and cheaper to resell and smuggle across borders. As a result, these items are often resold through several intermediary distributors before they are finally exported to Russia.

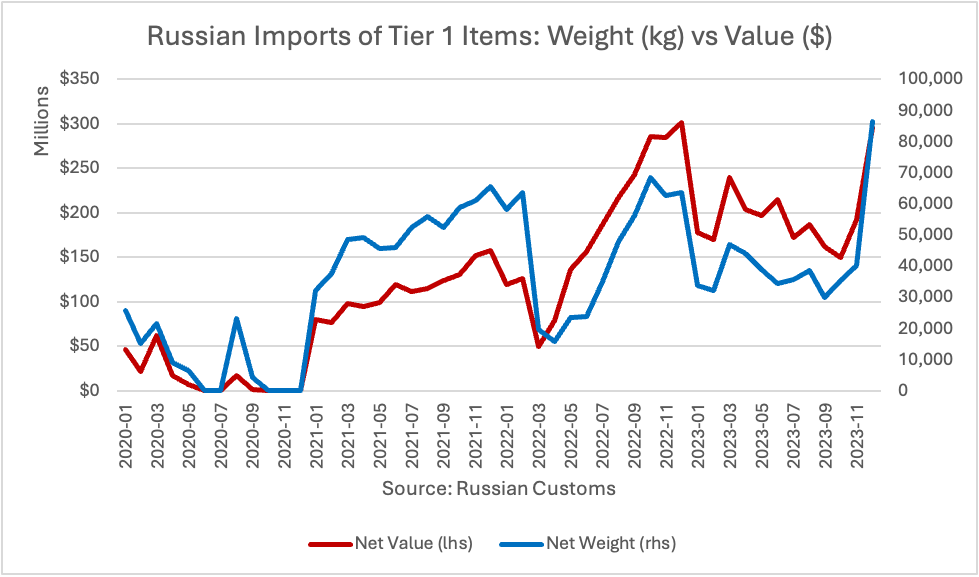

While the trade data shows that the export control and sanctions measures cannot completely stop Russia from gaining access to components from U.S. and U.S.-aligned countries, they do impose a cost on Russian companies by increasing procurement costs. One indicator for this is that while the net value of Russia’s imports of Tier 1 items has increased in customs data, the net weight of these items has slightly decreased from pre-invasion trends (see Figure 6). Thus, Russia is paying more for its imports (see Figure 7).

Figure 6

Figure 7

Another indicator is that Russia is willing to expend significant state resources to establish procurement networks of these items through third countries. The case of an Estonian-based network apparently run by the FSB was particularly high-profile.

Faced with economic sanctions, increased military spending, and labor shortages, Russia has continued to experience a rising level of inflation, forcing the Russian Central Bank to raise interest rates to over 15%.

Despite attempts at import substitution, Russia will continue to rely on chips made in U.S. and U.S.-aligned countries in the foreseeable future. Attempts by China to increase domestic chip production indicate how complex it is to establish a primarily domestic chip manufacturing supply chain without the help of partner countries. Russia is also likely drawing down any existing supplies of microchips it procured before the invasion. Persistent and improved export controls enforcement can play a key role to slow down Russia’s economic and military aims.

*Note on data sources: Some customs data sources report a sharp drop in imports from Hong Kong starting March 2023. In this data, imports from Hong Kong are replaced by imports Malaysia, Taiwan, Vietnam, USA, and Thailand replaced imports from Hong Kong. However, adjusting for the location of the supplier shows that Hong Kong-based suppliers continued supply almost all these imports.